World War II: European

World War II: European

by LTC JD Lock

The Second World War saw the dawning of the modern Ranger organization.

Darby’s Rangers: 1st, 3rd, 4th Ranger Infantry Battalions

In the spring of 1942, the U.S. Army Chief of Staff, General George C. Marshall, sent Colonel Lucian K. Truscott, Jr., to London to arrange U.S. participation in British Commando raids against German occupied Europe. In that U.S. ground forces had yet to engage German soldiers, Marshall intended to have men selected from across a broad spectrum of units gain combat experience alongside their British allies. These soldiers would be trained by the commandos and participate in combat operations under British command. Once trained and exposed to combat, the U.S. soldiers would be reassigned to their original units with new, inexperienced soldiers sent to replace them. This rotation of trained and inexperienced troops would lead one to believe that the original intent in regards to the Rangers was not to create a unit of unique and highly skilled light fighters…which it would ultimately become.

On 26 May 1942, the newly promoted Brigadier General Truscott recommended to the Chief of Staff that an American unit be organized along similar lines as the British Commandos. Wanting a unit similar in capability as the British Commandos, General Marshall authorized the formation and activation of a U.S. Army commando-type organization. Upon his return, Truscott conveyed to Major General Russell P. Hartle, commanding general of the U.S. Army Northern Ireland Forces and U.S. Army V Corps, Marshall’s directive to organize the new unit as quickly as possible.

On 1 June, Major General James E. Chaney, commanding general of the U.S. Army Forces British Isles, forwarded a letter titled, “Command Organization,” to Major General Hartle. In this letter, Chaney provided guidance for the organization of an American “commando unit for training and demonstration purposes.” This was to be “the first step in a program specifically directed by the Chief of Staff for giving actual battle experience to the maximum number of personnel of the American Army.” The selection criteria for volunteers specified that only fully trained soldiers of the best type were to be accepted. Organized in Northern Ireland, the battalion-sized unit would be attached to the British Special Services Brigade for tactical control and training. The U.S. 34th Infantry Division would provide logistic and administrative support.

During one of his trips to Washington, D.C, Truscott had discussed with then Major General Dwight D. Eisenhower?who was the chief of Operations Division War Department General Staff?the possibility of activating a U.S. commando-type unit. Eisenhower’s recommendation was to use a select a name that was not closely associated with British special forces. After some thought, Truscott decided that, in honor of Rogers’ Rangers, the official designation of the unit would be the 1st Ranger Battalion.

The legendary William Orlando Darby was selected to command the 1st Ranger Battalion. Darby?previously Hartle’s aide-de-camp and newly promoted?was given a free hand to organize, man, and equip his battalion. On 7 June, a letter to the 1st Armored Division, 34th Infantry Division, and other major commands was sent from Hartle, informing them of the Ranger Battalion’s formation. Authorized to choose volunteers from any military unit then in Ireland, Major Darby began the selection process on 8 June when he began to interview his first officer volunteers.

The 1st Ranger Battalion was formally activated on 19 June 1942 on the parade field at Carrickfergus with a strength of twenty-nine officers, 488 enlisted. The battalion was organized into a headquarters company and six line companies. The line companies consisted of two platoons, each platoon having two assault sections and a 60-mm mortar section. The Rangers were lightly armed with M-1 rifles, .30-caliber machineguns…which would be replaced by Browning Automatic Rifles (BAR), 45-caliber submachineguns, and 60-mm mortars at platoon level. The lightness of their weapons was to enhance their mobility.

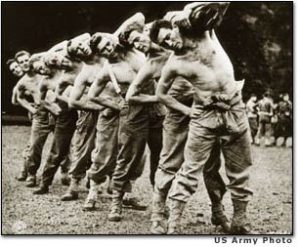

Fully manned and equipped by 28 June, the 1st Ranger Battalion moved to the British Commando Depot at Achnacarry, Scotland, where they would remain until 31 July. Training was tough, stressful, and as realistic as possible: assaulting positions under directed live fire, swimming ice, cold rivers, and cliff climbing?all with full pack, numbing road marches for time, beach-landings, basic soldiering skills, and unarmed combat. These were only a few of the many ordeals the new Rangers endured under the guidance and supervision of the British Commandos.

From the beginning, Darby strongly emphasized a concept that is still very much alive within the Ranger organization today: the buddy system. Allowing the soldiers to choose their own buddies, Darby required these small groups to work in pairs. They would eat, perform details, and train as a team. It is a concept that has stood the test of time and combat.

Fifty Rangers became the first American soldiers to fight the Germans on land in the Second World War on 19 August 1942 during a Canadian led amphibious assault on the English Channel port of Dieppe, France. The attack was poorly planned and badly executed. The assaulting Allied forces suffered horrendous losses and were decisively defeated. Overall the attack cost the Canadian Division seventy-five percent of its force killed, wounded, or captured within six hours. Despite the overwhelming odds, the Rangers who fought at Dieppe lived up to the highest expectations and won the admiration of their seasoned and more experienced British Commando comrades with whom they fought side by side. Ranger losses for this operation were two officers and four enlisted men killed, seven wounded, and four captured?an American loss of thirty-four percent.

Departing England in October, the 1st Ranger Battalion’s official entry into the war occurred on 8 November 1942, as part of Operation Torch…the invasion of North Africa. The initial mission was to seize two batteries that threatened the landing sites north of Arzew, Algeria. Following Arzew, the 1st Ranger Battalion did not see combat for nearly three months. During February and March 1943, the battalion was involved in several major actions. On 11 February, Companies A, E, F, and a battalion headquarters element, all under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Darby, conducted a night raid against Italian front-line positions near station de Sened in central Tunisia. During the period 16 February to 1 March, the Ranger Battalion conducted patrols from their defensive positions south of Bou Chebka. On the evening of 13 March the Rangers attacked and secured Gafsa in support of Major General George S. Patton, Jr.’s II Corps. A week later, late on 20 March, the Ranger Battalion infiltrated enemy lines along a tortuous ten-mile route through the heavily mountainous terrain to successfully attack from the rear and secure the Djebel el Ank Pass from a heavily entrenched Italian force.

On 19 April 1943, Marshall authorized the activation of the 3rd and 4th Ranger Battalions based on Darby’s request and Eisenhower’s endorsement. Using members of the 1st Battalion as cadre, the 3rd and 4th Ranger Battalions were activated. Major Herman W. Dammer, the 1st Ranger Battalion’s executive officer, was selected to command the 3rd Ranger Battalion and provided Companies A and B of the 1st Battalion to assist with building the new unit. Captain Roy A. Murray, Jr., the former F Company commander, was selected to lead the 4th Ranger Battalion and provided Companies E and F for his nucleus. Darby retained command of the 1st Ranger Battalion, which kept Companies C and D. In that Darby’s request for a Ranger Regimental Headquarters had been denied, Darby ‘simply’ attached the 3rd and 4th Battalions to the 1st and remained a battalion commander with the duties and responsibilities of a regimental commander. These three battalions would be designated “Ranger Force.”

Spearheading Patton’s Seventh Army amphibious landings on 10 July 1943 after only six weeks of training the new regiment, Darby’s 1st, 3rd, and 4th Ranger Battalion Ranger Force landed as the lead elements of Operation Husky, the invasion of Sicily. The 1st and 4th Ranger Battalions…designated “Force X” and attached to Major General Omar Bradley’s II Corps…made an opposed landing at Gela.

Force X captured the town and then defended it against a German and Italian armored counterattack. Darby personally played a part in the defense of the city and for his heroism at Gela, Darby was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross.

The 3rd Battalion was attached to Major General Lucian Truscott’s 3rd Infantry Division and conducted an opposed landing approximately fifteen miles west of Licata. With the expansion of the beachhead, the 3rd Ranger Battalion conducted a ‘reconnaissance in force’ and overran an enemy position and secured the surrounding heights near Highway 118, capturing 165 Italian prisoners. Moving toward the town of Montaperto, the Battalion ambushed an Italian motorized column and destroyed it. From Montaperto, the Rangers attacked, cleared and secured Porto Empedocle.

During the drive to Palermo, the 1st, 3rd, and 4th Ranger Infantry Battalions redesignated as such on 1 August-of Ranger Force were employed as conventional infantry. Following Messina’s capture on 17 August, the Ranger Force assembled at Palermo to begin preparation for the invasion of Italy.

Operation Avalanche found Ranger Force landing in advance of the Fifth Army’s invasion at Mairori, Italy, a location 20 miles west of Salerno. Attached to the British X Corps, the Rangers achieved total surprise prior to daylight on 9 September. After securing the town and destroying nearby coastal defenses, the Ranger Infantry Battalions quickly moved inland and seized the critical Chiunzi Pass by mid-morning. A slow breakout from the beachhead by Fifth Army forced the Rangers to hold the strategic pass for more than two weeks against repeated German counterattacks and sustained artillery fire until relieved on 28 September, suffering nearly twenty percent casualties in the process.

Following a drive on Naples, Ranger Force was employed as conventional infantry on the Winter Line, enduring bitter winter mountain fighting near San Pectro, Venatro, and Cassino. On 16 January 1944, the Ranger Force was designated the 6615th Ranger Force (Provisional). As a result, a Regimental Headquarters element was authorized that provided Darby a staff and a greater degree of control over the three Ranger Infantry Battalions. Having been promoted to colonel on 11 December, Darby now had his title of regimental commander.

Ranger Force was withdrawn from the line to prepare and to train for an amphibious landing at Anzio. The invasion at Anzio commenced before dawn on 22 January 1944. Once again leading the way, the 6615th Ranger Force (Provisional) seized the port facilities, reduced enemy defensive positions, and secured the beachhead for follow-on forces. Darby was ordered to have his Ranger Infantry Battalions to seize and to hold the town of Cisterna and its vital road junctions until relieved by 30 January. The Ranger Infantry Battalions were replaced on the line the morning of 29 January-contrary to the Ranger’s opinion that enemy resistance at Cisterna had the potential to be considerable.

At 0100 the next morning, both the 1st and 3rd Ranger Infantry Battalions crossed the LD. The terrain between the LD and Cisterna was flat farmland with little cover or concealment. Moving along a previously reconnoitered route, the 1st and 3rd Battalions used a drainage ditch that provided cover and concealment to avoid enemy detection. The 4th Ranger Infantry Battalion crossed the LD at 0200 and advanced on the Conca-Isola Bella-Cisterna road toward Cisterna.

Despite breaks in contact and isolated enemy contact, the presence of the 1st and 3rd Ranger Infantry Battalions seemed to remain undetected throughout the early morning hours but as daylight approached, their luck ran out when they were met by overwhelming fire from the town only four hundred yards from the town’s edge. Stopped in their tracks, the Rangers returned fire as best they could from a position astride a road leading into Cisterna.

On the Conca-Isola Bella-Cisterna road, the 4th Ranger Infantry Battalion attempted to reinforce its sister battalions but met heavy resistance. Stopped short of Isola Bella by heavy tank, self-propelled gun, automatic weapon, and small arms fire, the 4th was fought to a standstill and surrounded until the next day.

Outnumbered, outgunned, surrounded, confined to a perimeter three hundred yards in diameter, and attacked by armor, the 1st and 3rd Battalions were deluged by a storm of cannon, automatic, and small arms fire. Ranger attempts to escape the encirclement and German attempts to overrun their position were met with unrestrained ferocity on both sides. Two hours later and still continuing to hold on, the Rangers found themselves running low on ammunition.

Growing in strength as the Rangers were being bled dry, the Germans threw the newly arrived 2nd Parachute Lehr Battalion into the fray. Armor, antiaircraft batteries, and artillery in direct fire mode rained destruction down on the entrapped Rangers. Shortly after noon, recognizing that the end was near, the surviving Rangers began disassembling their weapons, burying or scattering key parts, and destroying communications equipment. The last man to speak with Colonel Darby from Cisterna was the sergeants major of the 1st Battalion, Robert Ehalt. He informed Darby that the 1st Battalion commander was wounded, the 3rd Battalion executive officer dead, and German tanks were closing in. Concluding his conversation with “So long Colonel, maybe when it’s all over I’ll see you again,” Ehalt destroyed the radio and continued to fight for a while longer with the few Rangers left before finally surrendering.

Broken into smaller and smaller units of resistance, some Rangers continued to fight it out only to be captured or annihilated in detail. By the end of the day, the 1st and 3rd Ranger Infantry Battalions had ceased to exist, having been completely annihilated. Of the 767 Rangers who reached Cisterna, only six made it back to American lines, the remainder were either killed or captured.

The Ranger’s concerns regarding the operation had been realized. The Germans had concentrated considerable strength in Cisterna area of operation in preparation for a German counterattack on 2 February, to include reinforcing elements of the vaunted Hermann Goering Panzer Division on the evening of 29 January. Despite their destruction, though, the Ranger Force extracted a heavy price for their eradication, inflicting over 5,500 German casualties and seriously disrupting the planned German counterattack on the beachhead, thus forcing its execution back by two critical days. This additional forty-eight hours proved to be the difference for the American forces, for the German counterattack failed by only the narrowest of margins.

The battle at Cisterna proved to be the beginning of the end for Darby’s Ranger Force. After helping to turn back the German counterattack of 4 February, and a later one on 19 February, the Ranger survivors were assigned to conduct a scouting and patrolling school outside of Civitavecchia, Italy, for the Fifth Army. On 6 May, approximately 150 veteran Rangers of long standing were returned to Camp Butner, North Carolina, and remained there until the 1st and 3rd Ranger Infantry Battalions were inactivated on 15 August 1944 and the 4th Ranger Infantry Battalion on 26 October.

Following a few assignments, Colonel Darby requested and was assigned to the 10th Mountain Division, fighting in Italy, as the assistant division commander. While visiting the front in Torbole on 30 April 1945, a shell fragment from a German 88-mm gun killed him, days prior to the German surrender on 2 May. On 15 May 1945, Darby was posthumously promoted to brigadier general, the only Army officer to be posthumously promoted to general officer rank during the entire war.

29th Provisional Ranger Infantry Battalion

Following the departure of Darby’s Rangers from England to the Mediterranean, there continued to be a desire for a Ranger-type organization that could conduct raids on Fortress Europe. Theater headquarters authorized the organization of a new Ranger Infantry Battalion in September 1942 to replace the deployed 1st Rangers.

On 20 December, the 29th Provisional Ranger Infantry Battalion commanded by Major Randolph Milholland was formed. Manned by volunteers from the 29th Infantry Division, the battalion underwent rigorous training at Tidworth Barracks, England, and at the Commando Training Depot. Completing amphibious assault training in February 1943 at Bridge Spean and having won the admiring respect of both Lord Lovat, the famed British Commando, and the approval of Brigadier General Norman Cota…the 29th Infantry Division assistant division commander, the 29th Battalion was attached to the Number 4 Commando at Dartmouth for six weeks.

After conducting three joint raids on the Norwegian coast, the battalion moved to Bude, Cornwall, in May, and then to Dorlin House, Scotland, in July. The battalion participated in a fourth raid on Ile d’Ouessant…Ushant Island?off the tip of Brittany. The small number of Rangers accompanying the Commandos acquitted themselves very well. Moving to Dover in August, the battalion was deactivated at Okehampton, Devon, on 18 October 1943 and its soldiers returned to the 29th Infantry Division when it was determined to be no longer needed with the pending arrival of the 2nd and 5th Ranger Battalions from the U.S.

2nd, 5th Ranger Infantry Battalions

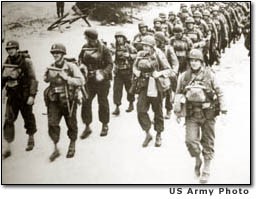

The two other European Theater Ranger Infantry Battalions, the 2nd and 5th Ranger Infantry Battalions, were officially designated the Provisional Ranger Group on 6 May 1944. Under the command of Lieutenant Colonel James Earl Rudder, these two battalions…referred to by some as “suicide squads”…had their baptism of fire on the beaches of Normandy on D-Day, 6 June 1944, as part of Operation Neptune, the amphibious phase of Operation Overlord.

The 2nd Ranger Infantry Battalion had been activated on 1 April 1943 at Camp Forrest, Tennessee. On 21 November, the battalion sailed for England. Activated at Camp Forrest, Tennessee, 1 September 1943, the 5th’s training started 14 September. Following a plan of instruction similar to the 2nd’s, the battalion trained in Florida and New Jersey prior to deploying to England early January 1944.

The 2nd’s mission was the toughest, most desperate, and dangerous mission of any of the D-Day assaulting units: three of its companies, D, E, and F, were to land seven kilometers west of the right flank of Omaha Beach on a narrow strip of beach at the base of Pointe-du-Hoc…has also been spelled Pointe-du-Hoe…scale the 120-foot sheer cliffs under heavy enemy fire, cross the mines and obstacles on top, and destroy six 155-mm cannon located in open, reinforced concrete casemates. Noted Lieutenant General Omar Bradley of Lieutenant Colonel Rudder, “Never has any commander been given a more desperate mission.”

The remainder of the Ranger force would wait offshore under the command of newly promoted Lieutenant Colonel Max Schneider. If the assault force under Rudder took possession of Pointe-du-Hoc, the code phrase “Praise the Lord” would be transmitted and the force under Schneider would move by boat to the Pointe to reinforce the position. If the message was not received by 0700, Schneider’s force would move to the Dog Green and Dog White sectors of Omaha Beach, move through the Vierville Draw, and proceed overland to assist their fellow Rangers at the Pointe.

The plan had been for the 2nd Rangers to hit the base of the cliff at 0630, just moments after heavy naval suppressive fires were lifted. It was hoped that the Rangers could scale the cliff before the defenders could reoccupy their defensive positions after having been driven by the suppressive fires into the protection of underground bunkers. Unfortunately, that would not be for the Rangers, impacted by heavy seas and errant navigation, arrived thirty-five minutes late.

Disembarking from their beached boats, Rudder’s men assaulted across the gradually narrowing strand of land to the base of the cliff. Taking heavy machinegun fire from a position located on their left flank, the Rangers quickly lost fifteen, dead or wounded. Reaching the ropes, the Rangers began their arduous climb up the suspended rigging.

Not anticipating an attack on their position from the sea, the German defenses facing the Rangers were the weakest. As the Rangers climbed, the Germans tossed grenades over the cliff and cut three or four of the ropes. Within five minutes of starting the climb, the first Rangers were secure on top to be followed in another ten minutes by the bulk of the fighting force.

At approximately 0730, the message “Praise the Lord” was broadcast from Pointe-du-Hoc, indicating that the Rangers had successfully scaled the cliffs. With less than two hundred Rangers left to drive on with the attack on top of the cliff, Colonel Rudder’s signal to his floating reserve, A and B Companies, 2nd Ranger Infantry Battalion, and the 5th Ranger Battalion to reinforce at Pointe-du-Hoc was transmitted fifteen minutes too late. The reserves had moved on to assault Omaha at 0715 in accordance with their established contingency plans.

Ignoring the machine gun and 20-mm cannon fire directed at them, the Rangers moved through the shell craters and German trenches toward the six heavy gun casemates. Closing on their mission objective, they were stunned to find that the ‘guns’ were, in reality, telephone poles. Fresh tracks running inland indicated that the six weapons had been recently removed.

Patrols were sent out to reconnoiter the area. Following heavy tracks of the missing artillery pieces for nearly 250 meters down a dirt road, three Rangers located the six missing cannons. Well camouflaged and prepared to fire on Utah Beach, the weapons were stocked with piles of ready ammunition and their gun crews were beginning to reform approximately 100 meters away. Within minutes, all six cannon were destroyed, along with a nearby ammunition supply point. By 0900, the 2nd Ranger Infantry Battalion became the first United States forces to accomplish their mission on D-Day.

For the next forty-eight hours, the Rangers were relatively on their own and still isolated. Armed with nothing more than BARs and 60-mm mortars, the siege of the surrounded Rangers continued as the Germans attempted to retake the fortified area with a series of counterattacks throughout the 6th of June and into the next day. But, despite their desperate situation, the Rangers held. By the end of the battle on 7 June, having fought nonstop for two days without relief, only 25 percent of the original force?fifty Rangers?were still capable of fighting when finally relieved.

Ten years later, during the reunion at Normandy, Colonel Rudder returned with his son to revisit the site. At the base of the Pointe, he looked up the towering cliff and asked, “Will you tell me how we did this? Anybody would be a fool to try this. It was crazy then, and it’s crazy now.”

Companies A and B of the 2nd Ranger Infantry Battalion were attached to the 5th Ranger Infantry Battalion. C Company 2nd Ranger Infantry Battalion was prepared to land at H+03 minutes in sector Dog Green of Omaha Beach on the far right flank of the assaulting units, only two minutes after the first wave.

At 0645, the Company C Rangers hit the shore at the far western edge of Omaha Beach, out of position just west of the Vierville Draw, sustaining over fifty percent casualties before they even made the beach. More than two kilometers from the nearest supporting troops, the Rangers were isolated and on their own. Though isolated and without radio communications, the Rangers continued the fight that eventually provided attacking elements the opportunity to force the Vierville Draw.

The 5th Rangers and the two attached Ranger companies from 2nd Battalion rode the channel tides waiting for Rudder’s message from Pointe-du-Hoc. Schneider waited until the appointed time of 0700 for the “Praise the Lord” message. The time came and went but the Ranger continued to hold his position. Finally, at 0715, he could delay no longer. The flotilla of twenty LCAs turned to make their run Omaha Beach.

Reports indicated that only one reinforced battalion of the German 716th Infantry Division was defending both the Omaha and Utah Beach sectors. The defenders were believed to be of minimum quality and standard with no reserves available for local counterattacks.

Unfortunately for the attacking force, this assessment was in total error. An experienced German infantry division, the 352nd, had been moved to the coast early that spring and assigned a sector that was inclusive of Omaha Beach. The net result was a doubling of forces in the area, a soldier of higher standard, improved command and control, and a mobile reserve positioned only five miles from the beach.

The two Ranger companies of the 2nd Ranger Infantry Battalion approached first. As the ramps dropped, the German defenders opened fire, unloading on the disembarking Rangers with a heavy concentration of fire. The fires were intense and some Rangers took nearly thirty minutes to struggle through the water to reach the beach. Offshore, Schneider observed the overwhelming struggle and carnage faced by the 2nd Ranger Infantry Battalion companies. Realizing that the landing effort had been “a disaster,” he elected not to wastefully throw his battalion away. Ordering the remaining fifteen LCAs to move east down the coastline, he found a quieter, relatively speaking, sector of Dog Red and commenced his assault at 0745.

![]()

![]()

Enemy resistance had greatly exceeded expectations. By 0830, all landings at Omaha Beach were halted and Lieutenant General Omar Bradley was seriously considering redirecting the follow-on forces to one of the other beachheads. Over 5,000 soldiers were trapped on the beach with nearly 50 percent of them lying wounded or dead on the shore. Body parts…headless torsos, arms, legs…floated in the surf. Groups of exhausted, confused, and frightened soldiers huddled wherever they could find some cover or concealment. Equipment was stacked on the waterfront and vehicles that were not already hit and burning were immobilized with nowhere to go, inviting targets for the ranging mortar and artillery rounds.

Though it would seem at that moment that the Allied war had been lost on Omaha Beach, there was American resistance and movement. Tanks of the 741st Tank Battalion, the first to arrive at Omaha, put up a stiff fight despite their inability to get over the shingle at the beach’s edge. Caught between rising waters and German anti-armor fires against their exposed positions, the tankers continued to engage the over-watching enemy pillboxes until either taken out of action by a hit or flooded out by the incoming tide. Individuals and small groups bypassed the heavily defended beach exits and began to move directly off the beach by moving straight up the bluffs. Bravely moving onward, these courageous soldiers passed “many dead bodies, all facing forward.”

Realizing that the situation was critical and that his forces must clear the beachhead, the assistant division commander of the 29th Infantry Division and first general officer to the beach, Brigadier General Norman D. Cota, set about moving his troops inland. Cota served as an inspiration to all who saw him on that bloody day. Shortly after arriving on the beach, he gathered a group of men and led them through a mortar barrage across the beach and up the bluff. Reaching the top of the bluff at a point midway between St. Laurent and Vierville and meeting some resistance, Cota organized his group into fire and maneuver teams that drove the German defenders to flight.

Progressing along a dirt road that ran parallel to the beach, the general moved through and secured the town of Vierville. On the western edge of the town, he dispatched a twenty-three-man patrol of Rangers that had joined him in the direction of Pointe-du-Hoc. Encountering stiff resistance, the Rangers’ movement was nearly stopped until Cota moved forward to assist the Ranger platoon leader Lieutenant Parker, with the disposition of his element. This group of Rangers would be the group that’d link up with the 2nd Battalion at Pointe-du-Hoc around 2100 later that evening.

Needing to get back to the beach, Cota moved to the Vierville Draw accompanied by his aide and four riflemen. Still heavily defended by German troops, the draw had just finished being pounded by the Texas’s secondary armament of 5-inch batteries when Cota’s small group arrived to find German troops quickly moving from their bunkers and reoccupying their positions. Observed and fired on by some of the defenders, Cota’s group was able to capture five German prisoners who showed them a safe passage through the minefields of the draw that allowed all to safely reach the beach.

Under constant machinegun and sniper fire from the bluffs, Cota continued to move about the beachhead, ordering, cajoling, herding, and reorganizing units, telling his soldiers, “Don’t die on the beaches, die up on the bluff if you have to die, but get off the beaches or you’re sure to die.” Moving from group to group, he came across one of his sons’ West Point classmates, Captain Raaen, commander of the 5th Ranger Battalion Headquarters Company (HHC). Directed to Schneider’s command post (CP), the general commented to Raaen, “You men are rangers and I know you won’t let me down.”

Locating the Ranger Infantry Battalion’s CP, Cota remained standing. Schneider stood to speak with the general. Cota asked of the men around him, “What unit is this?”

Schneider replied, “We’re Rangers, sir!”

With that, Cota yelled, “Rangers, lead the way off this beach before we’re all killed.” Thus was born what would eventually become the official motto and mantra of the 75th Ranger Regiment…”Rangers Lead the Way”

As events would have it, the Rangers were in the final stages of preparation to break out of the beachhead when Cota arrived at their location. Moving forward, Corporal Gale Beccue of B Company and an accompanying private, shoved an M-1Al bangalore torpedo…a five foot section of steel tube filled with TNT and amotal…under some barbed wire to blow a gap in the obstacle.

Lieutenant Francis W. “Bull” Dawson was tossed on top of a barrier wall by some of his men. Charging through more wire, Dawson destroyed a machinegun nest, cleared trenches of German defenders, and secured prisoners. The lieutenant’s efforts inspired the rest to follow. For his actions, Dawson would be awarded the Distinguished Service Cross.

Having breached the main German defenses on the beach, the Rangers then advanced up the bluff, encountering little opposition along the way. However, the push was not without its moment of levity. For a brief period, members of the Headquarters Company donned their chemical protective mask in belief that the heavy smoke from a brush fire might be gas. The cure nearly turned out to be greater than the “disease,” for some men nearly suffocated, having forgotten to pull the plug on the front of the mask that allowed air to circulate through it to breath.

Cresting the top, Schneider deployed his battalion to the left and right flanks and dispatched a unit to move four miles down the road to seize Vierville. To the front lay open fields and a maze of hedgerows from which German machineguns took the Rangers under fire. The failed aerial bombardment earlier that morning would prove to be costly to the attackers. Breaking up into smaller assault groups, the Rangers and other members of the 116th Infantry Regiment who had also made it to the top had to move forward across intermittently open ground to engage and to outflank the enemy defensive positions. The breakout from Omaha Beach had begun.

Following Normandy, the two Ranger Infantry Battalions were committed as conventional infantry to help reduce the defenses of the port city of Brest in September and to clear the Crown and La Conquet Peninsulas.

In December 1944, the 2nd Ranger Infantry Battalion deployed to the Heurtgen Forest, Germany, and seized Hill 400 overlooking the Schmidt and Roer dams that previous regular infantry attacks had failed to secure. During the Battle of the Bulge, the battalion primarily conducted defensive operations. In January 1945, they trained replacements at Schmidthof, Germany. February found them crossing the Roer River and conducting security missions through April. They moved to Czechoslovakia in May to find themselves in Dolreuth at the war’s end. The 2nd Ranger Infantry Battalion was deactivated at Camp Patrick Henry on 23 October 1945.

The 5th Ranger Battalion through the remainder of 1944 found itself being used for long-range patrols and other conventional infantry operations. On the evening of 23 February 1945, the 5th Rangers infiltrated deep behind enemy lines and established a blocking position on the critical Irsch-Zerf road by 0830 on the 25th of February and were not relieved until 1500 on the 27th. This mission would prove to be the last major combat mission of any Ranger Infantry Battalion in the Second World War. This action by the 5th Ranger Battalion in the vicinity of Zerf, Germany, is considered to be one of the most successful Ranger operations of the war.

The 5th Ranger Infantry Battalion finished the final two months of the war fighting as conventional infantry conducting routine combat missions, guarding prisoners, and imposing military government in and around Bamberg, Erfurt, Jena, Gotha, and Weimar. Finally, on 2 October 1945, the 5th Ranger Infantry Battalion was deactivated at Camp Miles Standish, Massachusetts.